Demonstration of the Surface Tension Lowering of Water by Soaps/Detergents

Surface Tension:

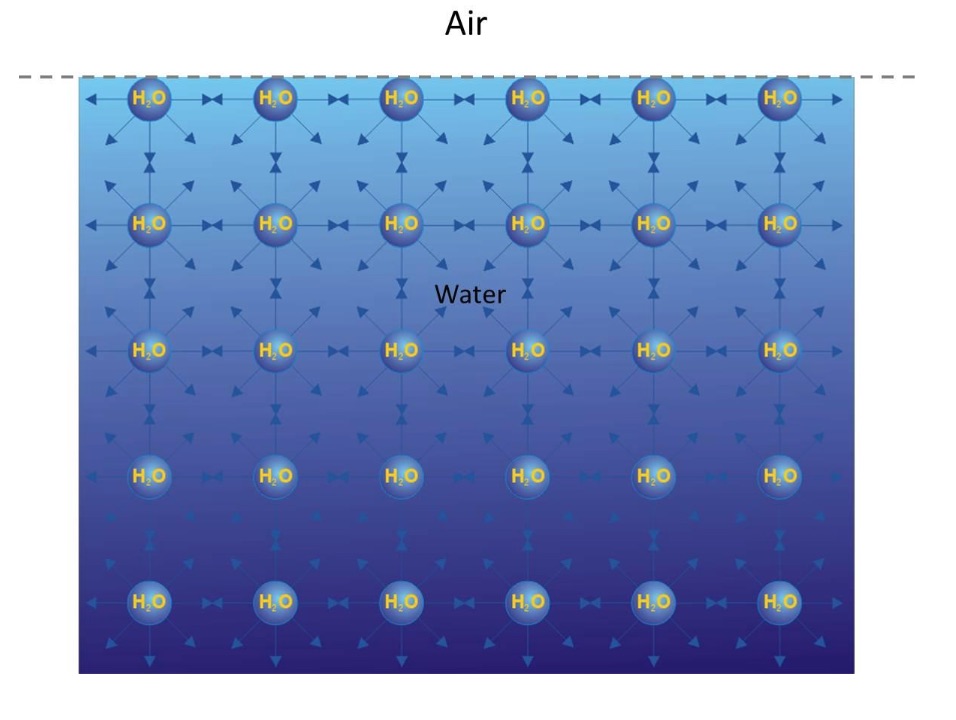

Surface tension results from the imbalance between the cohesive forces of surface and bulk molecules. The molecules within the bulk of a liquid are attracted uniformly in all directions by all neighbouring molecules. Therefore, the cohesive forces acting on the bulk molecules are uniform in all directions and a molecule within the body of a liquid will not experience a net force. The molecules at the liquid surface have almost no neighbouring molecules above them (since there are few vapour molecules and mainly air molecules above the liquid surface), therefore exert stronger attractive forces on one another at and below the surface. This imbalance in the intermolecular forces at the surface gives rise to a net inward force. This net inward force causes the molecules on the surface to contract and resist being stretched or broken from each other.

If an object is dropped onto the surface of water, it has to push the water molecules apart in order to sink into water. When the weight of the object is less than the surface tension effect, the object will not be able to penetrate the surface and therefore will lie on the surface of water. This is why several insects are able to walk on water. Their small weights are further distributed over the water surface via their legs allowing them to move across the surface of the water without breaking through the surface. Similarly, a carefully placed paper clip or a small needle floats on the surface of water even though the density of these objects is greater than water. The force of gravity pulling down these objects is balanced by the surface tension effect. Careful observation shows that the water surface gets slightly depressed like a stretchable membrane under the weight of the floating insect or needle.

The effects of surface tension become clearly visible if surfactants are added to water. Surfactants such as detergents and soaps are long chain hydrocarbon molecules with an ionic or polar group at one end. Such molecules are amphiphilic in nature: the long hydrocarbon chains being hydrophobic whereas the polar or ionic groups being hydrophilic in nature. The hydrophobic chains do not interact well with water molecules and tend to orient themselves at the interfaces pointing out of water. This considerably weakens the forces between water molecules, thus lowering the surface tension. This can be clearly observed if detergent or soap is gently added to the water where the needle or paper clip is floating. On addition of surfactants, the surface tension gradually decreases making the clip or needle sink through the surface under their own weights. The spreading of surfactants at the water surface can be visualised if some talcum powder (flakes) are sprinkled on the surface of water. When a drop of detergent is added to the powdered surface, initially the powder flakes are pushed to the edges very rapidly because the detergent molecules form their own surface monolayer. On further addition of surfactants, the powder begins to sink. This principle is used in the Hay test for jaundice. In this test, powdered sulfur is sprinkled on the urine surface. Sulfur powders float on normal urine (which has a surface tension of about 66 dynes/centimeter), but sinks if bile is present that lowers the surface tension of urine to about 55 dynes/centimeter.

If the water is hard water which contains a significant quantity of calcium ions (Ca2+), and/or magnesium ions (Mg2+), these cations initially form insoluble compounds with surfactant anions. Therefore, surfactants are precipitated out instead of forming a surface layer which could reduce the surface tension of water.

2 CH3(CH2)13COO− (aq) + Ca2+ (aq) → [CH3(CH2)13COO−]2Ca(s)

Therefore, hard water requires more soaps and detergents to reduce the surface tension of water.

In order to increase the surface area of a liquid of constant volume, work must be done or energy to be spent. Mathematically, if the work dw is done to increase the surface area of the liquid by an infinitesimal amount dσ, then

dw = γ dσ

where γ is the surface tension of the liquid. Values of surface tension in terms of the SI units can be given as J m-2 but are often quoted in equivalent N m-1 units. However, surface tension is typically measured in dynes/cm, the force in dynes required to break a liquid film of length 1 cm. For example, at 293 K for liquid-air interfaces, water has a surface tension of 72.8 dynes/cm compared to 22.3 dynes/cm for ethyl alcohol and 472 dynes/cm for mercury.

For a constant volume system, the work done dw is equivalent to the change in the Helmholtz free energy dA.

Therefore, one could also write dA = γ dσ.

The equation shows that the decrease in surface area decreases the free energy of a constant volume system. This explains why the droplets of water or bubbles tend to adopt spherical shapes, because for a given volume sphere has the smallest surface area.

Surface tension of a liquid is not constant. It depends on the temperature, pressure, presence of other impurities, etc. The surface tension typically decreases with increase in temperature (for example, water has a surface tension of 72.8 dynes/cm at 293 K compared to 58.0 dynes/cm at 373 K).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of molecular level interactions resulting in surface tension in liquid water. (Adopted from https://www.kibron.com/surface-tension).